Before he became an Olympic champion, Daniel Igali was just a boy in Bayelsa, wrestling barefoot in the sand and dreaming of a chance to fly on an airplane. Wrestling gave him that chance, and ultimately took him to Sydney 2000, where he made history as Canada’s first Olympic wrestling gold medalist.

Wrestling was more than a sport, it was a badge of honor. “The people you respected the most in town were the wrestlers,” he recalls. Like every other boy, he tussled after school in the village arenas, often returning home with a dirty uniform and the sting of his mother’s disapproval.

His mother, a professional teacher, wanted him focused on academics. His father, a chartered accountant, hoped he would follow a more conventional path.

Wrestling, at the time, offered no future. But Igali clung to it. By the age of ten, he was already dominating older boys, his strength and skill setting him apart. No

That same year, inspiration arrived in the form of an Olympian who had competed at the 1984 Los Angeles Games. He spoke of flying to Egypt for qualifiers and to America for the Olympics. For young Daniel, who thought Egypt was in heaven because of Bible stories, it was a revelation.

“I wanted to go to the Olympics because I thought that was the only way to fly by plane,” he says with a smile.

Despite his passion, Igali never abandoned his studies. At 17, he earned admission to the University of Jos, though financial constraints forced him to defer entry until one sibling graduated. Balancing academics with wrestling soon became punishing. Representing Nigeria at African Championships in the early 1990s often meant missing crucial exams.

Once, his coach had to plead with university lecturers to let him sit for delayed papers. “I was carrying over 11 courses before I left the country,” he recalls.

Still, wrestling held him fast. In 1991, just out of secondary school, Igali earned his first national team call-up for the All-Africa Games in Cairo.

It was his first time on a plane, his first trip abroad, and he returned home with a silver medal. Suddenly, the boy once punished for wrestling after school was a hometown hero, a symbol of possibility for younger kids.

The path to greatness was not without pain. The 1992 Olympic qualifiers nearly broke him. With little funding, athletes starved themselves to make weight and slept at Lagos airport, only for six names, excluding his, to be called when it was time to leave.

“That was the biggest disappointment I ever had as an athlete,” Igali admits. For two weeks, he stayed off the mat, questioning his future. But love for the sport pulled him back.

By the mid-1990s, Igali was a landed immigrant in Canada, studying and training. His heart, however, remained tied to Nigeria. He even offered to pay his way to the Olympic trials in 1996, but was not invited. When Nigeria skipped the 1997 World Championships in the U.S., he volunteered to compete but was again denied.

“By 1998, when I became a Canadian citizen, it was a no-brainer,” he explains.

Switching allegiance was not easy, but it proved the right choice. Canada welcomed him, not just as an athlete, but as a leader. He was given opportunities to coach, teach, and grow in the sport, chances he insists would have been impossible had he stayed.

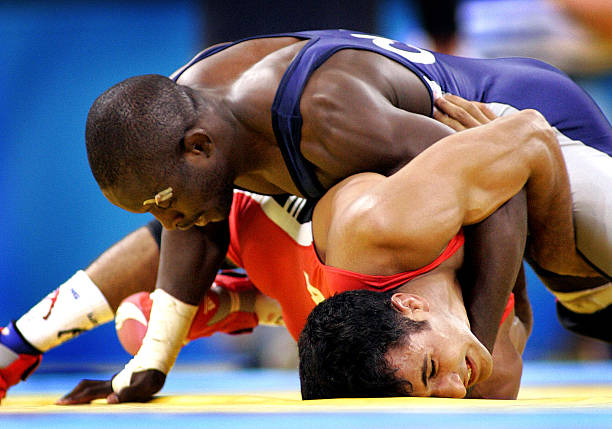

At the Sydney 2000 Olympics, Igali etched his name into history. Representing Canada, he wrestled his way to gold in the men’s freestyle 69kg category, Canada’s first-ever Olympic wrestling title. Beyond the medal, the victory was symbolic: the barefoot boy from Bayelsa had climbed to the very top of the sporting world.

His iconic celebration, wrapping himself in the Canadian flag, kneeling on the mat, and kissing it, remains one of the enduring images of Olympic spirit. Yet in his heart, Bayelsa and Nigeria were never far away.

Today, Igali straddles both worlds, balancing his identity as a Canadian champion and a Nigerian son. He has returned home to mentor young athletes, advocate for sports development, and fight for structures that support student-athletes.

“I’m glad everything worked out well,” he reflects. “If not for what Canada did for me, I wouldn’t be where I am today. But I’ve also been able to give back to Nigeria.”

From the creeks of Bayelsa to the mats of Sydney, Daniel Igali’s story is one of resilience, sacrifice, and vision. He represents what is possible when raw talent meets opportunity, when a dream born in a small village finds expression on the world stage.